If you have ever wondered why a correct diagnosis does not always translate into better outcomes, the answer is often not clinical skill. It is the data gap between what clinicians know and what health systems can reliably act on.

Health informatics exists to close that gap. It turns clinical observations, diagnoses, orders, labs, meds, and care plans into structured information that can travel across systems, trigger safety checks, support care coordination, and fuel analytics that help teams improve. In the United States, EHR adoption is near universal in hospitals, and the focus has shifted to interoperability, workflow quality, and patient access.

In this deep dive, you will learn how raw clinical information becomes actionable data from the first patient encounter through aggregation and analysis, and how that pipeline directly impacts safety, efficiency, and more personalized care. You will also see real world workflows, common failure points, and what high performing teams do differently.

Health Informatics In 2026

A helpful way to think about health informatics is that it sits between medicine and execution. It is the discipline that designs how health information is captured, standardized, exchanged, protected, and used for decisions.

Globally, the term digital health is commonly used as an umbrella that includes electronic records, telehealth, mobile health, and health data systems. The World Health Organization’s global strategy frames digital health as a way to strengthen health systems and improve outcomes when implemented thoughtfully.

In the United States, the last decade was dominated by EHR adoption. As of 2021, nearly all non federal acute care hospitals (96%) and nearly 4 in 5 office based physicians (78%) had adopted a certified EHR, according to ONC Quick Stats.

More recently, CDC survey results for 2024 reported 95.0% of U.S. office based physicians had adopted EHR systems and 83.6% were using a certified EHR system.

Now the limiting factor is not whether data is digital. It is whether it is usable, shareable, and trustworthy enough to change care in real time.

That is why interoperability and patient access have become central policy and operational priorities. For example, in 2023, 70% of non federal acute care hospitals engaged in all four interoperability domains (send, find, receive, integrate) either routinely or sometimes, but only 43% did so routinely.

Those numbers explain a lot. If data exchange is only occasional, outcomes improvements are harder to sustain because care teams still operate with partial context.

Core Pipeline: Turning Clinical Reality Into Actionable Data

Health informatics transforms outcomes through a repeatable pipeline. Each stage has its own technical details, but the logic is simple: capture accurately, standardize, exchange, govern, then use.

Step 1: Capture The Patient Encounter

The patient encounter begins as narrative, conversation, and physical assessment. Informatics translates parts of that reality into structured fields and coded concepts.

Examples of high value structured capture include:

- Problem lists and diagnoses coded for consistency (for example ICD 10 CM in the United States).

- Vitals, labs, and clinical measurements coded for interoperability (for example LOINC for lab and clinical observations).

- Clinical findings and conditions captured with clinical terminologies (for example SNOMED CT).

- Medications standardized using drug vocabularies (for example RxNorm in many U.S. health IT contexts).

Why this matters for outcomes: what cannot be represented consistently cannot be reliably checked, trended, or shared. A free text note can be clinically insightful, but it is a weak foundation for safety automation and population analytics.

Step 2: Validate, Reconcile, and Reduce Data Friction

Once data is captured, it has to be validated. This is where informatics teams prevent downstream harm.

Common validation and reconciliation activities:

- Medication reconciliation that aligns patient reported meds with pharmacy history and prior encounters

- Identity matching and de duplication so that labs and notes land on the right patient

- Mapping local codes to standards so results are comparable across sites

- Clinical documentation improvement workflows that reduce ambiguity for coding and quality measures

Outcomes link: reconciliation reduces gaps that cause medication errors, missed follow ups, and duplicated testing. This is also where operational efficiency improves because fewer people are forced to re enter or re interpret data.

Step 3: Standardize and Model The Data For Use

Standardization is not just about code sets. It includes the data model and how meaning is preserved.

In practice, this includes:

- Data dictionaries and definitions (what exactly counts as sepsis screening completed)

- Normalized representations (one definition of a blood pressure reading, not 12)

- Terminology services and mappings (SNOMED CT to billing classifications, lab test mapping to LOINC)

- Quality checks and provenance (where the data came from, when, and under what workflow)

This is where many organizations either win or lose. If the model is messy, analytics teams build dashboards that look confident but behave inconsistently.

Step 4: Exchange Data Across Systems

Interoperability is where patient outcomes often change the most, especially at transitions of care.

Key interoperability building blocks in 2026 include:

- HL7 FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources), a standard for exchanging health data through modern APIs and implementation guides.

- Patient access approaches, including APIs that let individuals access their health information through apps and portals, which ONC has tracked in both hospital capability and patient usage studies.

- Network to network exchange governance efforts like TEFCA in the United States, designed as a nationwide “network of networks” for health information exchange.

This stage is where informatics “bridges the gap” in the most literal way. Without exchange, every care team is forced to behave like the patient has no history outside their walls.

Step 5: Use The Data

The final step is where outcomes change. Informatics enables data use in three main ways:

- Point of care decision support

- Operational and care coordination workflows

- Population analytics and quality improvement

A simple example: medication ordering is safer when orders run through computerized provider order entry (CPOE) with clinical decision support. In a landmark study, introducing computerized physician order entry was associated with a 55% decrease in non intercepted serious medication errors (from 10.7 to 4.86 events per 1000 patient days).

Another example is the broader category of electronic prescribing systems. A systematic review and meta analysis reported a 48% reduction in prescribing errors and estimated 17.4 million medication errors could be avoided annually in the U.S. with adoption of electronic prescribing.

The key point is not “technology fixes medicine.” The key point is that well designed informatics workflows make it easier for clinicians to do the right thing consistently.

The Standards & Policies That Make Outcomes Possible

Clinical Terminologies

When health systems cannot agree on meaning, they cannot coordinate at scale. Standards solve this.

Practical roles of core standards:

- ICD 10 CM supports consistent diagnosis coding in the U.S. and drives billing and reporting workflows.

- LOINC standardizes lab tests and clinical measurements so results can be exchanged and interpreted across systems.

- SNOMED CT supports consistent representation of clinical concepts in EHRs, which helps with analytics and exchange.

- RxNorm provides normalized names for clinical drugs and supports medication data consistency across systems.

- FHIR supports modern API based exchange patterns.

When these are implemented well, organizations can measure quality more accurately, trigger safer order checks, and share a usable care summary instead of a PDF.

Privacy & Security Rules

Outcomes depend on trust. Patients avoid care, withhold information, or disengage when they do not believe systems protect them.

In the U.S., the HIPAA Privacy Rule provides national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other personal health information and sets conditions on uses and disclosures.

In the EU, the GDPR treats health data as a special category of personal data with additional restrictions and conditions for processing.

From an informatics perspective, privacy and security are not just compliance tasks. They shape data availability, system design, auditability, and how confidently clinicians and patients use digital workflows.

Key Numbers To Ground The Conversation

Here are a few data points that matter for understanding what “transformation” looks like in practice:

- EHR adoption: As of 2021, 96% of non federal acute care hospitals and 78% of office based physicians adopted a certified EHR (ONC Quick Stat).

- Office based physicians, latest CDC survey: In 2024, 95.0% adopted EHR systems and 83.6% used a certified EHR system.

- Hospital interoperability, 2023: 70% of hospitals engaged in all four domains (send, find, receive, integrate) routinely or sometimes, but only 43% did so routinely.

- Patient portal access, 2024: 77% of individuals reported being offered online access to their medical records, and 65% were offered and accessed their records.

- App based access trend: App based access to online medical records increased from 38% in 2020 to 57% in 2024.

- Caregiver access trend: Proxy or caregiver access increased from 24% in 2020 to 51% in 2024.

- Medication safety example: Computerized physician order entry was associated with a 55% decrease in non intercepted serious medication errors (from 10.7 to 4.86 events per 1000 patient days).

Notice what these numbers imply. We have widespread digitization, growing patient access, and improving exchange, but routine interoperability and practical usability remain the differentiators.

Real World Application

To make this concrete, here is a realistic workflow that many hospitals attempt, with informatics as the backbone.

What The Clinician Sees

A nurse documents vitals, a clinician orders labs, and the EHR shows a rising risk score. An alert prompts a sepsis screening protocol. The care team responds quickly with fluids, cultures, and antibiotics when appropriate.

What Informatics Builds Behind The Scenes

- Data capture and standardization

- Vitals are captured as structured fields

- Labs are coded consistently (often using LOINC mappings)

- Data integration

- The patient’s prior encounters, recent discharge summary, and outside labs are retrieved through exchange when available

- If the organization participates in broader exchange networks, informatics teams configure interfaces and governance for those flows (for example TEFCA participation in the U.S. context).

- Logic and decision support

- The rule logic is validated for sensitivity and false positives

- Alerts are routed to the right role at the right time

- Overrides, acknowledgements, and outcomes are logged for evaluation

- Analytics and improvement loop

- The team monitors time to antibiotics, time to fluids, ICU transfers, and documentation completeness

- The informatics team reviews alert burden, missed cases, and documentation artifacts that degrade performance

Where Outcomes Actually Improve

Outcomes improve when the workflow reduces time to action and reduces variability. That usually comes down to:

- Reliable data capture

- Real integration of outside records, not just the capability to do it

- Decision support that is specific enough to be trusted

- A feedback loop where the build is adjusted based on observed performance

This is why “informatics transforms outcomes” is best understood as a systems engineering statement, not a marketing slogan.

How Health Informatics Improves Efficiency

Efficiency in healthcare is often framed as cost reduction, but informatics driven efficiency is more about removing waste that harms care.

High impact examples include:

- Reducing duplicate testing by making outside results available at the point of care (interoperability and integration).

- Streamlining medication workflows with safer ordering, allergy checks, and interaction checks, which can reduce downstream error handling.

- Improving patient self service through portals and apps, which can reduce friction for scheduling, refills, results review, and clinical note access in many organizations.

An important nuance: efficiency gains that ignore user experience backfire. Poorly designed EHR workflows can increase clinician burden, leading to workarounds that harm data quality. Informatics teams that focus on outcomes treat usability as a safety issue, not a “nice to have.”

Personalized Treatment Plans: What Informatics Actually Enables

Personalization is often misunderstood as meaning AI generated treatment. In practice, informatics enables personalization in more grounded ways:

- Risk stratification using longitudinal data, such as prior admissions, comorbidities, and medication history

- Care gap identification for preventive care and chronic disease management

- Precision in medication management through accurate medication lists and standardized drug data (RxNorm alignment improves consistency across systems).

- Shared decision making by giving patients access to notes, results, and care plans through portals and apps, which has expanded materially over the past decade.

This is personalization as operational reliability. The goal is that the right plan follows the patient, and the next clinician does not have to start from scratch.

Common Mistakes And How To Avoid Them

Health informatics projects fail in predictable ways. Here are the most common mistakes I see, and what to do instead.

Mistake 1: Treating Interoperability As An Interface Project

Many teams connect systems but fail to make the data usable in workflow. The 2023 ONC data brief highlights the difference between “sometimes” exchange and “routine” exchange, and that gap often reflects workflow integration failures.

How to avoid it: Design for the receiving clinician. Build reconciliation, display, and trust cues. Measure whether outside data is actually used at the point of care.

Mistake 2: Ignoring Terminology and Data Definitions

If every clinic uses different names, different picklists, and different “completed” states, your analytics becomes fragile.

How to avoid it: Invest early in governance, data dictionaries, and terminology management. Use standards where appropriate (LOINC, SNOMED CT) and document local mappings.

Mistake 3: Building Alerts Without Managing Alert Burden

Clinical decision support can improve safety, but it can also create noise and override culture.

How to avoid it: Start with high severity, high specificity use cases. Monitor overrides. Treat CDS like a product with ongoing iteration, not a one time build.

Mistake 4: Neglecting Patient Access and the “Many Portals” Problem

In 2024, 59% of individuals reported having multiple online medical records or portals, and only 7% used a portal organizing app to combine information.

How to avoid it: Simplify patient navigation. Make APIs and portal workflows consistent. Use education and encouragement, since ONC data shows encouragement is associated with higher portal use.

Mistake 5: Treating Privacy and Security As Separate From Outcomes

Security incidents can disrupt care delivery and degrade trust. Even outside of incident scenarios, privacy rules shape data flow design.

How to avoid it: Design with minimum necessary access principles, auditability, and strong governance from day 1. Anchor decisions in HIPAA and relevant privacy frameworks in your operating regions.

Looking Ahead

Health informatics transforms patient outcomes by doing something deceptively hard: turning clinical reality into data that can be trusted, shared, and used at the moment decisions are made.

In 2026, the story is no longer “EHRs are coming.” The story is that EHR adoption is widespread, patient access continues to rise, and interoperability is improving, but routine, workflow integrated exchange is still the differentiator.

If you want to assess your own organization or your own career path in this space, start with three questions:

- Are we capturing data in a structured way that preserves meaning

- Can we exchange and integrate external information routinely, not occasionally

- Do our decision support and analytics actually change behavior in a measurable way

Answer those honestly, and you will know whether informatics is merely “installed” or truly improving outcomes.

Latest Articles on Informessor

How Health Informatics Transforms Patient Outcomes

If you have ever wondered why a correct diagnosis does not always translate into better…

Healthcare Data Quality Framework to Fix Broken Dashboards

If you have ever shipped a dashboard you were proud of, only to watch it…

ChatGPT Health Breakdown: The Most Important Health Product of the Decade?

The next decade of healthcare will not be won by the flashiest sensor or the…

Fixing Emergency Department Delays: How Health Informatics Can Help

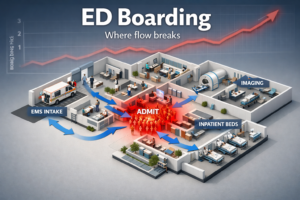

Walk into almost any busy emergency department and you will feel it before you measure…

Wellness App or Medical Device? How Wearables Cross The Line

Wearables are no longer just tracking habits. They are shaping decisions. The same sensor that…

AI in Drug Discovery & Clinical Trials: How Far Have We Come?

Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and clinical trials has been sold as a cure for…

References

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). National Trends in Hospital and Physician Adoption of Electronic Health Records. Health IT Quick Stat #61. 2021. Published on HealthIT.gov.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics. NEHRS Results and Publications (2024 results summary). 2025-12-14. Published on CDC.gov.

- ASTP, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Interoperable Exchange of Patient Health Information Among U.S. Hospitals: 2023. Published on HealthIT.gov. 2024.

- ASTP, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Individuals’ Access and Use of Patient Portals and Smartphone Health Apps, 2024. Published on HealthIT.gov. 2024.

- Health Level Seven International (HL7). HL7 FHIR Overview and Specifications (FHIR and versioning pages). Published on HL7.org. Accessed 2026.

- ASTP, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. TEFCA overview page. Published on HealthIT.gov. Updated through 2026.

- Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. 45 CFR Part 172, Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). Updated 2024-12-16. Published on eCFR.gov.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020-2025. 2021. Published by WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. Digital health: transforming and extending the delivery of health services. 2020-09-09. Published on WHO.int.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil Rights. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Published on HHS.gov.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR), provisions on special categories of personal data including health data. Published on EUR Lex.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ICD 10 CM diagnosis coding overview resources. Published on CDC.gov.

- Regenstrief Institute. LOINC overview and purpose for identifying health measurements, observations, and documents. Published by Regenstrief Institute.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM). SNOMED CT overview and U.S. health IT context. Published on NLM.nih.gov.

- SNOMED International. What is SNOMED CT. Published on SNOMED.org.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM). RxNorm description and purpose for normalized clinical drug names. Published on NLM.nih.gov.

- Bates DW, et al. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. 1998. Published in JAMA.

- Radley DC, et al. Reduction in medication errors via electronic prescribing, meta analysis and annual avoidable errors estimate. 2013. Published in Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.