In hospitals, healthcare data is not just a record of what happened. It is the input that drives orders, billing, staffing, quality reporting, and the daily decisions that keep patients safe. When that data is wrong, incomplete, duplicated, or delayed, the impact rarely stays small. A single typo in demographics can split a patient into 2 records, a missing problem list item can weaken clinical decision support, and a documentation mismatch can trigger a denial that ties up cash and staff time. Over weeks and months, those small cracks turn into measurable harm, waste, and mistrust.

This article breaks down how bad data shows up inside real hospital workflows, why it spreads, and what it costs in patient care and finances. It sticks to verified evidence and widely used standards, and it keeps the focus on practical cause and effect, not buzzwords.

Healthcare Data Gone Wrong

Bad data in a hospital usually starts in ordinary places: registration, transfers, medication history, problem lists, order entry, coding, and interfaces between systems. The issue is not that clinicians or staff do not care. The issue is that hospitals run on high volume, interruptions, time pressure, and many handoffs. When even one step is fragile, bad inputs pass downstream and become someone else’s problem.

One common pattern is fragmented identity. If a patient is registered with a nickname in one visit and a formal name in another, or if addresses and phone numbers vary across encounters, matching becomes harder. That can create duplicate or fragmented records, where allergies, immunizations, prior imaging, or current medications are split across different charts. Public health systems have documented how difficult patient matching and de duplication can be, and why fragmented records create risk when updates and queries land in the wrong place (CDC, 2025). Policymakers have also highlighted that failures in accurate patient matching can lead to unnecessary repeated tests because the system cannot reliably link the patient to the right medical record (U.S. Congress, 2024).

Another pattern is clinical documentation that is technically present but not usable. A medication might be listed, but the dose or route is unclear. A diagnosis might be captured in one part of the record but never makes it to the problem list that drives alerts and summaries. An abnormal lab may be filed correctly, but not associated with the correct clinical context. These issues often feel like minor usability or workflow problems, but they can become safety problems when clinicians rely on summaries, lists, and alerts rather than digging through every note.

Interoperability can amplify the problem. When data moves between systems, differences in formats, vocabularies, and required fields can turn a clean record into a messy one. The U.S. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology describes the United States Core Data for Interoperability as a standardized set of health data classes and elements meant to support access, exchange, and use of electronic health information (ONC, 2024). Standards help, but standards alone do not guarantee quality. If the data captured at the source is wrong, the exchange simply moves wrong data faster.

Patient Harm and Clinical Risk

Hospitals feel the patient safety costs of bad data most sharply in medication management, transitions of care, and identification errors.

Medication processes are especially sensitive to data quality because they depend on accurate lists, clear orders, and reliable reconciliation. The World Health Organization notes that unsafe medication practices and medication errors are a leading cause of injury and avoidable harm globally, and it has estimated the global cost associated with medication errors at $42 billion USD annually (WHO, 2024). That number reflects a worldwide burden, and it is not only a hospital issue, but hospitals carry a large share of the risk due to complex regimens and frequent handoffs.

Medication reconciliation is one of the most visible examples of how bad data turns into harm. The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals describe medication reconciliation as comparing what a patient should be taking and is actually taking with newly ordered medications, resolving discrepancies as care transitions occur (The Joint Commission, 2025). When the “home medication list” is incomplete, when a discharge summary is copied forward without confirmation, or when an outpatient pharmacy record is not available, the reconciliation step can become a guess under time pressure. That is how omissions, duplications, dosing errors, and interactions slip through.

Transitions of care are a high risk moment because information is moving and responsibility is shifting. AHRQ’s patient safety resources emphasize that transitions are associated with medication errors and adverse events, and they highlight how gaps in information exchange can jeopardize safety (AHRQ, 2024). Even when a hospital has strong clinicians, weak data at transitions creates predictable failure points: wrong medication continued, old medication stopped incorrectly, or follow up instructions that do not reflect what the patient actually has at home.

Patient identification errors sit in the background of many serious events. When a patient is misidentified, the risk is not only inconvenience. Orders, results, or histories can attach to the wrong person, and clinicians can miss critical context that would have changed a decision. The CDC’s de duplication guidance underscores that the inability to consistently determine which records represent the same patient creates fragmented and duplicate information, which undermines correct updates and queries (CDC, 2025). Policymakers have explicitly linked poor matching to unnecessary repeated tests and downstream costs (U.S. Congress, 2024). In a hospital setting, repeated testing is not just waste. It can expose patients to additional radiation, delays, and anxiety, and it can crowd out capacity for others.

There is also a quieter form of harm: degraded decision support. Clinical decision support depends on the right problems, allergies, labs, vitals, and medications being structured and current. If key details live only in free text or are entered inconsistently, alerts become noisy or incomplete. When alerts fire for the wrong reasons or fail to fire when needed, trust erodes. Clinicians then override more, and the system becomes less protective over time. The result is not one dramatic failure but a slow reduction in safety margin.

Financial and Operational Costs

Hospitals often feel the financial costs of bad data before they can fully measure the clinical ones, because revenue cycle systems, audits, and payer rules expose inconsistencies quickly.

A clear example is improper payments and payment errors tied to documentation and data accuracy. CMS reports improper payment rates and amounts across programs and describes how measurement programs track whether payments were made correctly under program requirements (CMS, 2024). For Medicare Fee for Service, CMS publishes improper payment data measured through the Comprehensive Error Rate Testing program and reports the overall improper payment rate and projected improper payment amount in its supplemental data (CMS, 2024). These payment errors are not all “bad data,” but weak documentation, missing information, and inconsistent coding are common contributors to whether a claim is paid correctly.

In Medicare Advantage risk adjustment, the link between data and dollars is even more direct. The HHS Office of Inspector General reported that diagnoses reported only on enrollees’ health risk assessments and related chart reviews, and not supported by other service records, resulted in an estimated $7.5 billion in Medicare Advantage risk adjusted payments for 2023 (HHS OIG, 2024). That finding highlights a core truth for hospitals and health systems: when clinical data becomes the basis for payment, the accuracy and support for each diagnosis matters. If a diagnosis is captured without adequate clinical evidence, organizations face payment risk, audit risk, and reputational risk.

Bad data also drives denials and rework. When a claim has missing identifiers, mismatched dates, inconsistent codes, or documentation that does not support medical necessity, it can be denied or delayed. Even if the hospital ultimately wins an appeal, the cost shows up as staff time, delayed cash, and distraction from patient care. The operational “tax” is the constant effort to hunt down missing information, correct coding, re bill, and explain what happened.

Operational costs extend beyond billing. Scheduling errors, duplicated charts, and interface failures create repeated work for clinical and administrative teams. When identity is fragmented, staff spend time searching for records, reconciling duplicates, and confirming whether two similar charts belong to the same person. When the medication list is unreliable, pharmacists and nurses spend extra time calling families, pharmacies, and outpatient clinics to reconstruct history. Those are labor costs, but they also create delays in care and longer lengths of stay in the most common situations: admissions, transfers, and discharges.

Bad data can also weaken quality reporting and performance improvement. Many hospitals report measures to regulators, payers, and accreditation bodies. If core elements are missing or not standardized, reporting becomes a manual, error prone process. HIMSS has noted that quality measurement programs can increase administrative burden and that data completeness requirements for measure submission can add pressure on organizations capturing and reporting data across multiple mechanisms (HIMSS, 2020). The more reporting relies on structured data, the more hospitals must treat data quality as part of care delivery, not a back office cleanup task.

Finally, data governance and interoperability rules create a compliance dimension. In the United States, the health data technology and interoperability rule landscape continues to evolve, including updates connected to information blocking policies and expectations around electronic health information access and exchange (Federal Register, 2024). While this is a U.S. specific example, the broader point is global: as regulation and trust frameworks increase, poor data hygiene becomes harder to hide. Whether the pressure comes from payers, regulators, national health systems, or public reporting, the costs rise when data cannot be trusted.

Why It Persists

Bad data persists in hospitals because the incentives and realities of hospital work often reward speed and local optimization over durable accuracy.

First, data is created at the edge of care. Registration staff, nurses, physicians, coders, and technicians each touch different parts of the record, often under time constraints. Small inconsistencies are normal in human work. The problem is when systems and processes do not catch them early. A weak front end validation rule, a confusing screen, or a workflow that encourages copying forward can turn one small inconsistency into a persistent defect.

Second, hospitals operate with many systems. Even when an organization has a primary electronic health record, it often has separate systems for lab, imaging, pharmacy, scheduling, billing, and specialty workflows. Interfaces can drop fields, map concepts incorrectly, or delay updates. When each system becomes a “source of truth” for its own domain, disagreements are inevitable. Without governance, teams spend their time negotiating which screen to trust rather than improving the underlying data.

Third, measuring data quality is harder than measuring volume. It is easy to count encounters, orders, or claims. It is harder to quantify whether problem lists are accurate, whether medication lists match reality, or whether identities are properly linked. The CDC has noted that accuracy and consistency are among the most difficult dimensions to assess compared with more straightforward checks like completeness and validity (CDC, 2015). If you cannot measure it well, it tends to lose priority to urgent operational metrics.

Fourth, the harm is distributed. The person who enters a demographic error rarely experiences the downstream denial. The clinician who clicks through an alert may not see the long term effect on safety culture. The unit that suffers the discharge delay may not control the upstream reconciliation process. Because the cost is spread across teams, it can feel like “everyone’s issue,” which often means no one owns it.

Finally, technology can create new failure modes. AHRQ has described how EHR usability issues and workflow mismatches can contribute to interruptions and distraction that increase the risk of error (AHRQ, 2024). Hospitals can digitize a broken workflow and scale it. If the system makes it easy to enter data quickly but hard to enter it correctly, speed wins, and quality suffers.

Fixing It With Governance and Workflow

Hospitals that reduce the hidden costs of bad data treat data quality as part of patient safety and operational excellence, not as an IT cleanup project.

The first step is to define what “good” means for the highest risk data. Not every field matters equally. Identity, allergies, active medications, active problems, key lab values, and key procedure history carry outsized risk. Standards like USCDI help clarify which data elements are foundational for exchange and use, but the hospital still has to decide which elements are safety critical internally (ONC, 2024). The practical move is to set clear definitions for accuracy, completeness, timeliness, and uniqueness for those elements, then design workflows that make the correct action the easy action.

Patient matching and record integrity deserve dedicated attention because they sit upstream of almost everything. The CDC’s best practices for patient level de duplication emphasize the need to ensure updates and queries apply only to the correct patient record and to prevent fragmented and duplicate information from being added to an individual’s health records (CDC, 2025). In a hospital, this often translates into consistent demographic standards at registration, stronger verification during high risk events like admissions and transfers, and routine duplicate detection and remediation with clear accountability. The goal is not perfection. The goal is to reduce preventable duplication and to handle inevitable ambiguity in a consistent way.

Medication reconciliation needs to be designed like a safety process, not a documentation checkbox. The Joint Commission recognizes the challenges organizations face with medication reconciliation and continues to emphasize it as a safety issue (The Joint Commission, 2025). The highest yield improvements tend to focus on making the medication history more reliable at admission and making the discharge list more usable for the next clinician and for the patient. That means ensuring sources are documented, discrepancies are resolved with evidence when possible, and the final list is clearly communicated across settings. It also means reducing copy forward habits that hide uncertainty.

Data governance is the structure that keeps improvements from fading. Governance is not a committee that meets to talk about data. It is a decision system that assigns owners for key data domains, sets standards, and funds fixes that reduce risk and rework. When governance works, clinical leaders and operational leaders agree on definitions and priorities, and IT implements changes that support the agreed workflow. Governance is also where hospitals decide how to handle conflicts between systems and how to manage data lineage so teams can trace a value back to its source.

Hospitals also benefit from building a feedback loop that is fast enough to matter. If a denial is caused by missing documentation, the fix should not be a one off appeal. It should feed back into the documentation workflow, template, or training so the same error becomes less likely. If duplicate records are found during a safety event review, that finding should feed into registration standards and matching procedures. The loop is what turns isolated firefighting into a declining error rate.

Finally, hospitals should be cautious about automation that depends on noisy inputs. ECRI has highlighted insufficient governance of artificial intelligence in healthcare as a patient safety concern (ECRI, 2025). The connection to data quality is direct: automated systems can scale the impact of wrong inputs. If a model is trained on inconsistent documentation or if an algorithm consumes incomplete problem lists, it can produce confident outputs that are wrong in systematic ways. The safest path is to improve the inputs, validate outputs against real clinical outcomes, and put governance in place before scaling automation.

The Real Cost of Bad Data

The hidden costs of bad data in hospitals are not hidden because they are rare. They are hidden because they are scattered across patient safety, revenue cycle, staffing, and day to day workflow friction. Bad healthcare data causes harm when clinicians cannot trust identity, medications, allergies, and problem lists at the moment of decision. It drains money when documentation gaps and inconsistencies create payment errors, denials, and audit risk. It steals capacity when staff must constantly search, reconcile, and correct what should have been right the first time.

The most effective response is not a one time cleanup. It is a shift in how hospitals treat data: as a clinical asset that requires ownership, standards, and feedback loops. When identity integrity, medication reconciliation, and core clinical documentation are designed for accuracy and supported by governance, hospitals reduce preventable risk and reclaim time and resources. The payoff is not only cleaner dashboards or smoother billing. It is safer care delivered with less friction.

More Articles on Informessor

The Hidden Costs of Bad Data in Healthcare

In hospitals, healthcare data is not just a record of what happened. It is the input that…

How Health Informatics Transforms Patient Outcomes

If you have ever wondered why a correct diagnosis does not always translate into better…

Healthcare Data Quality Framework to Fix Broken Dashboards

If you have ever shipped a dashboard you were proud of, only to watch it…

ChatGPT Health Breakdown: The Most Important Health Product of the Decade?

The next decade of healthcare will not be won by the flashiest sensor or the…

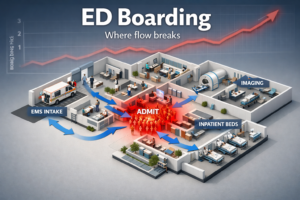

Fixing Emergency Department Delays: How Health Informatics Can Help

Walk into almost any busy emergency department and you will feel it before you measure…

Wellness App or Medical Device? How Wearables Cross The Line

Wearables are no longer just tracking habits. They are shaping decisions. The same sensor that…

References

CDC. (2015). https://www.cdc.gov/hearing-loss-children/media/pdfs/dataqualityworksheet.pdf

CDC. (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/iis/media/pdfs/2025/02/De-Duplication_Best_Practices_Report.pdf

CMS. (2024). https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fiscal-year-2024-improper-payments-fact-sheet

CMS. (2024). https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2024-medicare-fee-service-supplemental-improper-payment-data.pdf

ECRI. (2025). https://home.ecri.org/blogs/ecri-thought-leadership-resources/top-10-patient-safety-concerns-2025

Federal Register. (2024). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/12/17/2024-29683/health-data-technology-and-interoperability-protecting-care-access

HHS OIG. (2024). https://oig.hhs.gov/reports/all/2024/medicare-advantage-questionable-use-of-health-risk-assessments-continues-to-drive-up-payments-to-plans-by-billions/

HIMSS. (2020). https://www.himss.org/resources/changing-landscape-quality-measures-healthcare/

ONC. (2024). https://healthit.gov/standards-and-technology/onc-standards-bulletin/onc-standards-bulletin-2024-2/

ONC. (2026). https://isp.healthit.gov/united-states-core-data-interoperability-uscdi

The Joint Commission. (2025). https://digitalassets.jointcommission.org/api/public/content/9be383450fc941df806b76c5fbdd9ae6?v=3c600c3a

U.S. Congress. (2024). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/7379/text

WHO. (2024). https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm

AHRQ. (2024). https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/inpatient-transitions-care-challenges-and-safety-practices

AHRQ. (2024). https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/electronic-health-records