Wearables are no longer just tracking habits. They are shaping decisions. The same sensor that counts steps can also trigger a notification about a possible condition. The moment your product language or UX nudges a user toward diagnosis, treatment, or prevention, you are no longer shipping a wellness feature. You are shipping something regulators may treat as a medical device.

The wellness vs. medical device line is fading because wearables now combine continuous sensing with algorithms that users treat as clinical guidance. The FDA focuses on intended use, meaning what your labeling, marketing, and product behavior imply. When outputs can drive medical decisions, your evidence, claims, and compliance posture must level up.

Why The Wellness vs Device Line is Disappearing

3 forces are collapsing the old boundary.

First, sensors moved closer to clinical signals. Wrist worn sensors and motion data can be used to infer patterns that look like health conditions, not just lifestyle.

Second, software now interprets, not just displays. A chart is passive. A notification that implies risk changes behavior.

Third, distribution is instant. A single release can put a new health function in millions of hands overnight.

The key point: the FDA does not regulate your code in isolation. It regulates intended use and risk.

How The FDA Actually Draws The Boundary

Regulation follows intended use.

In FDA terms, intended use is objective intent, and it can be shown by labeling claims, advertising, or oral or written statements by the people responsible for the product. (Ecfr)

So the line is shaped by what you say and what your product does, including onboarding, feature names, notifications, and website screenshots.

Two FDA pillars are especially relevant for wearables.

General wellness policy for low risk devices

The FDA has guidance describing a compliance policy for low risk products that promote a healthy lifestyle. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

Device software functions and mobile medical applications

The FDA describes oversight for the subset of software functions that present greater risk if they do not work as intended, reflected in its policy guidance and updates. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

A practical boundary checklist

The general wellness guidance is often misunderstood as a blanket exemption. It is narrower. It explains a compliance policy for low risk products that promote a healthy lifestyle, and it explicitly does not apply when a product’s intended uses go beyond general wellness intended uses. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

This is why language matters more than most teams expect. Consider the difference:

- “Helps you understand sleep patterns” usually reads as wellness.

- “Detects sleep apnea” reads as diagnosis.

- “Assesses risk of sleep apnea” reads as a risk notification or assessment claim, which can still be regulated, as seen in the Apple clearance pathway. (FDA Access Data)

Now the checklist:

- Disease language or disease intent

If you claim detection, diagnosis, treatment, mitigation, or prevention of a condition, you are signaling device intent. - Clinical substitution

If your copy implies users can replace standard testing or avoid care, risk rises quickly. - Clinically managed metrics

Blood glucose and blood pressure are not just numbers. They are management inputs, and errors can cause harm. - Call to action that looks like triage

The more you tell users what to do medically, the more you look like a medical function.

Case Study 1: Blood Glucose Claims And The Reality Check

On February 21, 2024, the FDA issued a safety communication telling consumers not to use smartwatches or smart rings to measure blood glucose levels. The agency stated it has not authorized, cleared, or approved any smartwatch or smart ring intended to measure or estimate blood glucose values on its own. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

The reason is straightforward: inaccurate readings can lead to dangerous diabetes management errors, including taking the wrong dose of insulin or other glucose lowering medications. (Reuters)

Also notice the nuance. The FDA warning distinguishes these unapproved devices from smartwatch apps that display data from FDA authorized glucose measuring devices that puncture the skin, such as CGMs. (Reuters)

What this signals for product teams

If your feature touches a clinically managed metric, assume regulators will evaluate it through a harm lens, not a novelty lens.

Case Study Two: Sleep Apnea Notifications And The Shift Into OTC Risk Assessment

On September 13, 2024, the FDA cleared Apple’s Sleep Apnea Notification Feature through a 510(k) submission, listed as K240929, with the classification name Over The Counter Device To Assess Risk Of Sleep Apnea. (FDA Access Data)

The intended use is tightly scoped. Apple’s submission emphasizes that the feature is not intended to provide instantaneous measurements and is not intended to replace diagnostic methods like polysomnography, assist clinicians in diagnosing sleep disorders, or be used as an apnea monitor. (FDA Access Data)

It is also backed by clinical evidence. The 510(k) summary describes validation in a prospective, non significant risk study enrolling 1,499 subjects across several US sites. (FDA Access Data)

What teams can copy

- Narrow the claim to risk, not diagnosis

- Put limitations in the core UX, not in buried legal text

- Treat clinical validation as a launch gate for any feature that changes care seeking behavior

- Design outputs for clinician conversations, not self treatment

Case Study 3: Blood Pressure Insights And The Enforcement Temperature Rising

On July 14, 2025, the FDA issued a warning letter to Whoop, stating that its Blood Pressure Insights feature was being marketed without required FDA clearance or approval and describing the product as adulterated and misbranded. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

Coverage around the dispute highlights the core tension: a blood pressure estimation feature can be framed as wellness, but users interpret blood pressure numbers as medical, and the FDA emphasized it had not authorized the feature for any use. (Android Central)

The operational lesson

Disclaimers do not reliably control intended use when the output looks like a clinical metric and the marketing implies accuracy.

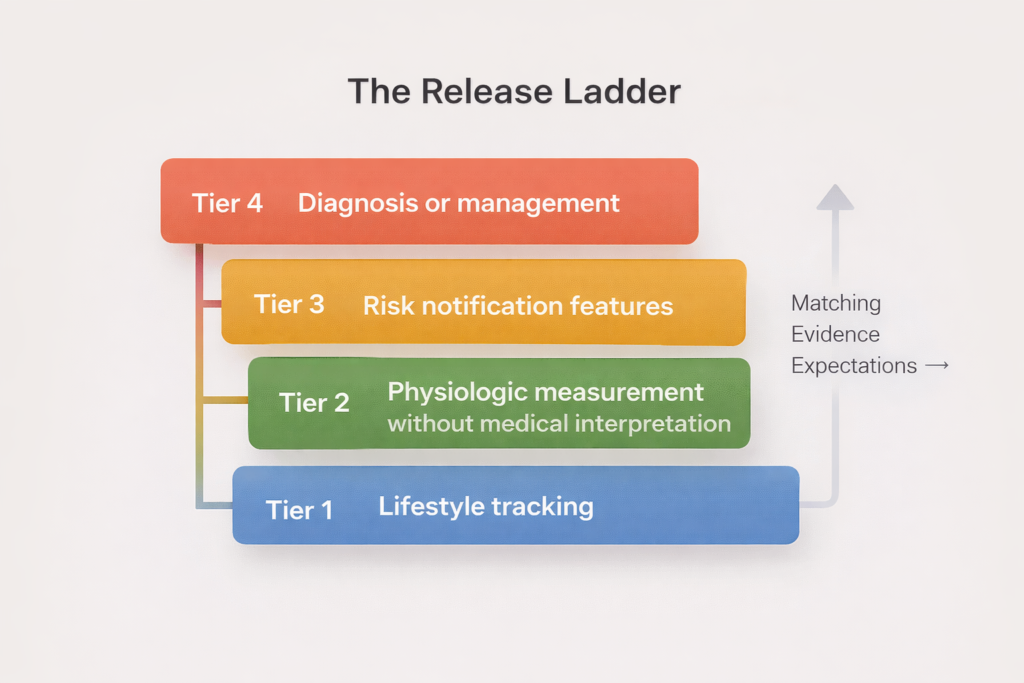

The Release Ladder Playbook For Health Wearables

As your claim climbs, your evidence and compliance must climb with it.

Tier 1: Lifestyle tracking

Examples: steps, activity minutes, general sleep duration.

Evidence: sensor characterization, usability testing, clear limitations.

Tier 2: Physiologic measurement without medical interpretation

Examples: heart rate trends, respiratory rate trends, temperature deviation metrics framed as wellness.

Evidence: analytical validation, error bounds, subgroup performance.

Tier 3: Risk notification features

Examples: irregular rhythm notifications, sleep apnea risk notifications.

Evidence: clinical validation, human factors testing for notifications, monitoring plan.

Tier 4: Diagnosis or management

Examples: blood pressure measurement, blood glucose measurement, medication guidance.

Evidence: rigorous clinical studies and safety controls.

How evidence scales with the ladder

Tier 1 and Tier 2 are mostly analytical validation: sensor characterization, stability, and error bounds in real conditions.

Tier 3 shifts into clinical validation: alignment with a clinical reference in the intended population, with predefined endpoints and metrics clinicians recognize.

Tier 4 is safety validation: proving the system is reliable and fails safely when wrong.

Where SaMD fits

When a wearable feature is software that performs a medical purpose, it can fall under Software as a Medical Device. The FDA points to the IMDRF definition of SaMD as software intended for one or more medical purposes that performs those purposes without being part of a hardware medical device. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

Wearables often sit in a hybrid reality: consumer hardware with software functions that may still be regulated when intended use and risk align. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

A claims rewriting mini playbook

If your team wants to stay in a lower tier while you gather evidence, rewrite claims to remove disease intent. Examples:

- Instead of “detects diabetes spikes,” avoid independent glucose estimation entirely unless you have authorization. The FDA’s glucose safety communication shows how aggressively it treats unauthorized glucose claims. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

- Instead of “diagnoses sleep apnea,” use “notifies of possible signs of moderate to severe sleep apnea,” but only if you are ready to validate clinically and align the UX to encourage professional evaluation, which is the pattern reflected in the Apple sleep apnea clearance. (FDA Access Data)

A minimal launch checklist you can run every release

- Claims inventory

Collect every place the feature is described and reduce it to one intended use statement. - Harm map

Write the top three ways a user could be harmed if the feature is wrong, including false reassurance. - Evidence match

Define what validation is required for the claim tier. Apple’s 510(k) summary shows how study design becomes part of the product story. (FDA Access Data) - UX guardrails

Ensure wording, visualizations, and notifications do not imply diagnosis if you do not have that indication. - Model governance

Track versions, data provenance, drift, and rollback triggers, and document subgroup performance.

What This Means For Founders, Data Scientists, And Clinicians

One more nuance for teams building clinician facing experiences

If you provide recommendations, triage, or interpretations aimed at clinicians, you start overlapping with clinical decision support. The FDA has separate guidance clarifying the types of clinical decision support software functions that are excluded from the device definition under the Cures Act criteria, and what falls inside oversight. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

In practice, that means your export formats, dashboards, and summaries matter. A graph can be informational. A statement like “patient likely has condition X” can be treated as a medical purpose depending on context.

High leverage habits by role

Founders: make compliance a product capability

- Add a “claims gate” in your release process where marketing, product, clinical, and legal all sign off on user facing language.

- When you decide to pursue clearance, treat it like fundraising: timeline, documentation, and stakeholder alignment.

Data scientists: build models that can survive scrutiny

- Define reference standards up front. If you cannot name the clinical comparator, you cannot validate the claim.

- Pre register metrics. For a notification feature, agree on acceptable false negative and false positive rates before you train.

- Track performance slices tied to real world variability, including motion and population subgroup differences.

Clinicians: protect patients while embracing useful signal

- Ask whether the feature is intended for people with a diagnosis or for screening. Apple’s sleep apnea materials, for example, scope intended use and limitations clearly. (FDA Access Data)

- Encourage confirmatory testing when outputs imply disease risk.

- Report patterns of misuse. If patients are changing medication based on consumer estimates, that is a safety signal the product team must hear.

FAQ

Is a disclaimer enough to stay in wellness

Not by itself. Intended use can be inferred from labeling, advertising, and statements, not just a footer. (Ecfr)

Can software only features be regulated

Yes. The FDA regulates certain device software functions and mobile medical applications when they meet the device definition and present higher risk. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

Why did the FDA speak so strongly about glucose wearables

Because inaccurate glucose readings can cause immediate harm, and the FDA emphasized it has not authorized any smartwatch or ring that measures or estimates glucose on its own. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

What is a clean pattern for risk notifications

Scope the claim narrowly, validate clinically, and design the UX to encourage professional evaluation. The Apple sleep apnea notification clearance is a concrete example. (FDA Access Data)

The Durable Rule For Wearables

The word wellness is no longer a protective label. People treat clinical looking outputs as guidance.

The durable rule is this: when your wearable output can change medical decisions, your process must look like medical product development. Climb the Release Ladder on purpose. Match claims to evidence. Design UX to prevent misinterpretation. And remember that intended use is written as much by marketing and product as by engineering.

More Articles on Informessor

The Hidden Costs of Bad Data in Healthcare

In hospitals, healthcare data is not just a record of what happened. It is the input that…

How Health Informatics Transforms Patient Outcomes

If you have ever wondered why a correct diagnosis does not always translate into better…

Healthcare Data Quality Framework to Fix Broken Dashboards

If you have ever shipped a dashboard you were proud of, only to watch it…

ChatGPT Health Breakdown: The Most Important Health Product of the Decade?

The next decade of healthcare will not be won by the flashiest sensor or the…

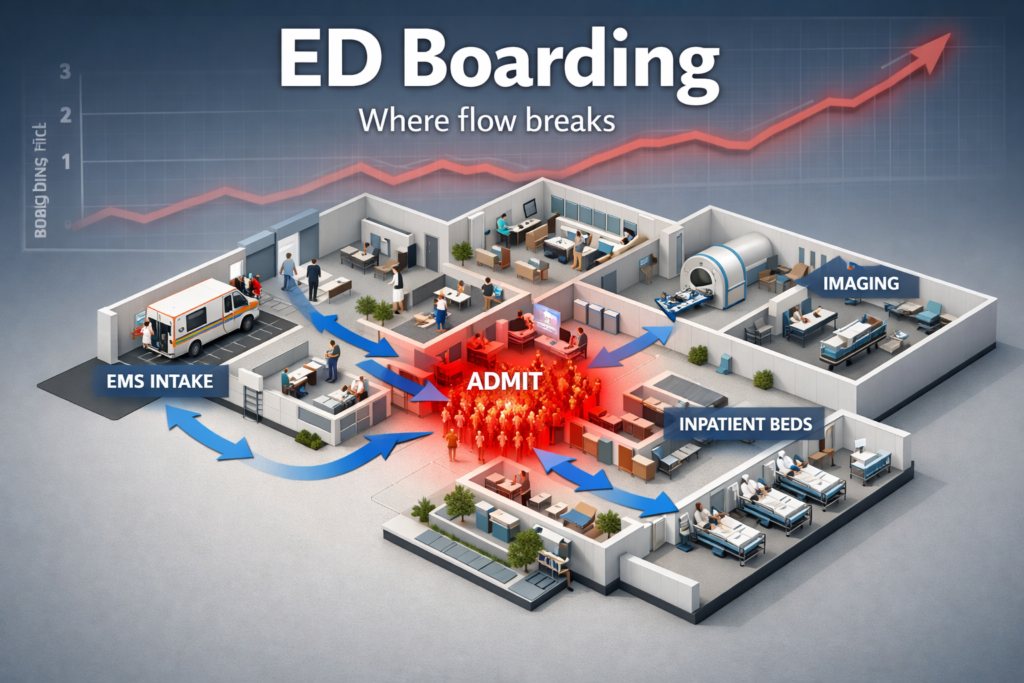

Fixing Emergency Department Delays: How Health Informatics Can Help

Walk into almost any busy emergency department and you will feel it before you measure…

Wellness App or Medical Device? How Wearables Cross The Line

Wearables are no longer just tracking habits. They are shaping decisions. The same sensor that…

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2024, February 21). Do Not Use Smartwatches or Smart Rings to Measure Blood Glucose Levels: FDA Safety Communication.

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/do-not-use-smartwatches-or-smart-rings-measure-blood-glucose-levels-fda-safety-communication - U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2024, September 13). K240929: 510(k) Premarket Notification (Sleep Apnea Notification Feature, Apple, Inc.).

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K240929 - Apple Inc. (2024, September 13). Traditional 510(k) Submission: Sleep Apnea Notification Feature (SANF), K240929 (PDF).

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf24/K240929.pdf - U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025, July 14). WHOOP, Inc. Warning Letter 709755.

https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/whoop-inc-709755-07142025 - U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2019, September 26). General Wellness: Policy for Low Risk Devices (Guidance).

https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/general-wellness-policy-low-risk-devices - U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2022, September 28). Policy for Device Software Functions and Mobile Medical Applications (Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff).

https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/policy-device-software-functions-and-mobile-medical-applications - U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2022, September 28). Clinical Decision Support Software (Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff).

https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-decision-support-software - Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. (Current). 21 CFR 801.4: Meaning of intended uses.

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-H/part-801/subpart-A/section-801.4 - U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018, December 4). Software as a Medical Device (SaMD).

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/software-medical-device-samd - International Medical Device Regulators Forum. (2013, December 9). Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Key Definitions (IMDRF/SaMD WG/N10FINAL:2013) (PDF).

https://www.imdrf.org/sites/default/files/docs/imdrf/final/technical/imdrf-tech-131209-samd-key-definitions-140901.pdf - Arnold and Porter. (2025, September 5). FDA Warning Letter to Fitness Wearable Sponsor Signals Enforcement Risk for Blood Pressure Features.

https://www.arnoldporter.com/en/perspectives/advisories/2025/09/fda-warning-letter-to-fitness-wearable-sponsor - Duane Morris. (2025, July 23). FDA Issues Warning Letter Classifying Wearable Blood Pressure Monitor Device.

https://www.duanemorris.com/alerts/fda_issues_warning_letter_classifying_wearable_blood_pressure_monitor_device_0725.html - FDA Law Blog. (2025, August 5). What to Watch: WHOOP Warning Letter.

https://www.fdalawblog.com/2025/08/articles/warning-letter/what-to-watch-whoop-warning-letter/